Leaving the Puerto Vallarta area in Banderas Bay was not unlike leaving home. Cool Change had been there for nearly nine months. We had a party with our dockmates to say goodbye. The government of Mexico and the Mexican telephone company have the Banderas Bay as our permanent address. And leaving at the first of the year was even harder because the sailing season really kicks in then: the races, the free seminars on crossing oceans, the daily free yoga classes in the marina, the weekly free movies in the outdoor amphitheater, the nightly live music in the little town of La Cruz, and our favorite, the pad thai cart in the La Cruz zocolo on Wednesdays. You could stay in the Puerto Vallarta area forever. And many people do, living on their boat, sailing in one of the best sailing venues in the world whenever the wind seduces them, and enjoying all the activities designed for cruisers.

But it was time to go. There are more places to discover. Our plan this winter is to sail south, stopping at as many of the anchorages and marinas along the way that attract us, and arrive in Zihuatenejo, a little over 300 nautical miles south, by the beginning of the international Guitar Fest in early March. We are not in a hurry but we want to keep moving so we don’t miss anything for lack of time.

CABO CORRIENTES

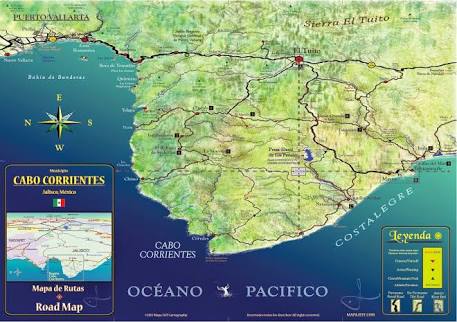

Cabo Corrientes is the most prominent point on the map on the west (left) side of mainland Mexico, defining the upper point of the where the coast changes direction making a sharp turn to the southeast

After getting lazy on land for several months, taking only short little sails for the day or spending the night on the hook once in a while, most sailors are ill-prepared for having to round Cabo Corrientes ads their first passage south. We tried our best to pick a good weather window and were as prepared as we could be, but we both found it a challenge. Here are our separate accounts of that 24-hour passage:

Rick’s Observations:

Cabo Corientes is a well respected point of land off the Mexican mainland just south of Banderas Bay. Much respect is given the weather when traversing this area in both directions.

A close up of Cabo Corrientes. They say to keep at least 5 miles off the coast because of the violent changes in currents that occur because of the land mass changes

We were about to take what is considered to be the “sleigh ride” route heading South from Punta de Mita to Chamela Bay. Prior to leaving we were chilling in the relative comfort of the marina of La Cruz in Banderas Bay, waiting for a good weather window. We actually stayed several days longer than expected, trying to get the best possible weather for what would be our first overnight passage in many months. The weather window we decided on called for NNW winds of 5 to 10 knots and seas of three feet. This sounded perfect as we were both feeling rusty and had not done any significant sailing in six months!

We set out for Punta de Mita the day before we were going to round Cabo Corientes because that would save us a couple of hours rather than leaving from La Cruz, and it was a good place to go to bid farewell to Banderas Bay. We spent a beautiful night at anchor there in very calm conditions as predicted. We had planned on leaving the anchorage at 0700, which would have us rounding Corrientes at about noon, ahead of the afternoon thermals and in about 14 knots of wind. When we left Punta de Mita, we were motor sailing as there was just a whisper of wind. We had a lovely drive by of the Tres Marietes islands early in the morning before any of the motorized tourist boats arrived.

As we rounded the islands on the inside of the bay, we decided to head out to sea about 15 miles to both take advantage of the better winds off shore and because when we finally turned south we should be able to set a heading to Chamela on a single tack.

Or so we thought…

As we were leaving Banderas Bay, we made radio contact with another boat that was heading south from Punta de Mita as well. They were Tom and Annie on Tapan Zee, a Coast 34, which they described as a Canadian knockoff of the renowned Valiant. We had met them previously in La Cruz marina and it was refreshing to learn that they loved to sail and especially loved doing multi day off shore passages. A good portion of the sailing cruisers we have met make no excuses for the fact that they don’t particularly enjoy sailing or passages! As such, they mostly motor to their destinations when they are on a coastal passage. Cindy and I much prefer to sail, and as a rule, we only start the engine when there is not enough wind and we find ourselves wallowing at something less than two knots for more than 30 minutes.

The weather started out very light and we decided to head out 15 – 20 miles off shore to round Cabo Corrientes. If the weather is strong, it is best to be out at least 5 – 10 miles to avoid the direct effects of the cape currents. In our light wind situation, we were heading out in hopes of getting a good push to get moving. As we headed further out to sea, the wind was behind us so we set the sails to a wing on wing configuration and let the sleigh ride begin! We had a very comfortable 16 knots true which kept us moving at 6-7 knots. Three hours later as we were nearing the point where we would turn ESE, the winds had built considerably to over 20 knots. By this time we had changed the configuration from wing on wing to a port tack. Expecting that we would be seeing more wind when we jibed to a beam reach, we put in a first reef in our headsail before making our turn for the run towards Chamela Bay.

As we made our to our new heading of 130M, we were surprised that the wind and sea were building much more than the weather predictions we had thoroughly researched. Cool Change was handling nicely though; we were surfing the 6 – 8 foot following sea. The helm felt comfortable as we flew along and it was easy to get into a steering rhythm. We were saving using the auto pilot for later in the night to conserve power. In hindsight we probably should have set up the wind vane steering early on but by now it was feeling a bit rough to be hanging over the stern setting it up so we decided to manually steer a couple hours then use the electronic autopilot the rest of the night.

We started our watch shifts at 19:00. As usual, the watch would be one person on deck for 3 hours while the other one slept below. This has worked well for us on prior passages and if one of us is overtired the next day they can nap during the daylight/ more casual watches.

During the night we had three close passes with ships, all closer than 2nm. The first was a cruise ship who we heard Tapan Zee hailing that at the time was over 10 miles behind us. Tapan Zee has receive AIS so they could see the ship approaching but they do not transmit a beacon for the ship to see them. At that time the officer on deck stated that they had Tapan Zee on Radar and mentioned they could see us on their AIS. They agreed to a heading they would be holding and eventually passed 1.8 miles off our port side between us and the shoreline. This was shortly before sunset.

Cindy had the 19:00 watch and I went below to get some rest. It was so bumpy though I was not really resting other than the fact that I was prone. I could tell things were getting bigger outside by the noise and movement of the boat and I popped up about 2100 to ask Cindy if she thought we needed to put in our second reef. She agreed, saying she had only been trying to hold off a little longer on that so I could get some rest. So we set about putting that second reef in the mainsail and jib before I went back below.

In setting the second reef, the main halyard got slack for just long enough to get on the wrong side of the spreader and a portion of the halyard got pinched between the mainsail and the standing rigging. To clear it I had to go forward to the mast, which is not the place you want to be in these conditions, but working together with Cindy in the cockpit and me at the mast, we cleared the problem and completed putting in the second reef.

By the time it was my first watch at 10pm we were well beyond getting any influence from Corrientes but the wind was a steady 25 knots gusting to over 30 with seas still around 8 ft. The helm still felt manageable though and the autopilot was working well. By this time, we had been set much closer to shore than we liked. We were 5nm off on a heading of 090. From our current position we were not going to make Chamela Bay on that tack so before Cindy went off watch we worked together to jibe the boat and head away from shore on a bearing of 190M. Though we would be closer to a beam reach than a deep broad reach we agreed we should re-rig the preventer while on this tack due to conditions so as not to chance an accidental jibe.

The system we use for a preventer is far from ideal as it requires a trip to the bow sprit to rig it each time we jibe to a new tack. Ideally we should have a system that would require going no further forward than the mid ship cleat but we have yet to work that out. We do have a second preventer line that can be rigged at the bow as well, theoretically allowing it to all be done from the cockpit, which will be our next experiment. I have been hesitant to use that system until now because of concerns over keeping control over the extra long length of line it would require but I think I am now ready to give it a try. I went to the bow and ran the preventer and eventually got back to the safety of the cockpit. By the time I returned, Cindy was distraught with worry because she can’t see me at the bow, we have no communication, and because it was so rough it took me much longer than normal to rig the preventer.

Her concerns were well founded because falling off the boat at night in those seas would offer a slim chance for recovery. Our only possible chance of even being located would be by activating the AIS locator beacon that we each carry on our life vest along with a water activated strobe light. When activated, the AIS beacon will send a signal to the AIS system aboard Cool Change and plot the person in the waters position right to our chart plotter. Once close enough the strobe could offer some visible confirmation of the persons position but in a swell of any serious proportion it would be difficult to see. In our US Sailing certification classes we practiced MOB drills at night in the relative calm of SF bay with a full crew complement and that was a challenge though nothing like what the real thing would be like under these conditions. In any event, I was tethered onto our jack lines and staying low and moving slow the whole time but it was no fun. I came back completely soaked after bathing in several waves that came over the bow, the only consolation being that the water was warm and even in the wind it was not terribly uncomfortable. Gotta love the tropics! If we were off of our home area of San Francisco I would have had hyperthermia before it was all over. So needless to say, this system is in need of upgrading and will be upgraded for safety!

Our battery voltage was getting low due to the extended use of the autopilot so we decided to start the engine to charge the batteries for awhile. Unfortunately, when I did so, the chart plotter and autopilot went down momentarily and took several minutes to re-boot and come back online. While the system was re-starting I was getting a string of error messages and it seemed an eternity before the autopilot finally re-engaged. When the chart plotter had fully reset I found that I had lost the touch screen capability. I remembered seeing a message about screen settings during the restart which I thought I selected correctly but apparently not! Though I hated to, I did not want to be dealing with trying to steer and correcting the issues with the chart plotter and autopilot so I called down to Cindy to come up and look at it. She was able to clear one issue but we were never able to get the touch screen back until we were at anchor and could go through the manual to find where to make the needed configuration changes.

We followed our new heading after Cindy fixed the chartplotter screen so it was usable, and then Cindy stayed on deck so we could douse the main and sail on the job alone. The winds by now had built even more. Even sailing on the Yankee jib seemed like too much power, so we deployed the staysail and furled in the jib. This worked well because with only the staysail flying we continued at 5 – 6 knots and did not have to be concerned with employing the preventer! In hindsight again, we could have done this much earlier but these are the lessons learned at sea that do not necessarily come out of books or classes. We completed over three years of training in our sailing program but as Cindy often says, the real training started when we left San Francisco and we started to put to use what we had learned. By now it was 03:00 and Cindy was exhausted so she went below for some much needed sleep. As I had disturbed her last rest time I told her not to come back to watch until I called her so hopefully she could get some extra time to recover her strength. She had gotten a bit seasick by this time as well and was sore from being thrashed about both on deck and down below. This had not been Cindy’s favorite passage and indeed was one of our more challenging nights at sea.

At 06:00 we checked in via SSB with Tapan Zee who during our sprint to get away from the shore had passed us and were now several miles ahead. They said all was good aboard and they planned on continuing to Zihuatenejo, another 300 miles down the coast. That was our last radio contact with them until we heard them check in via the amigo net at 08:00. About this time I noticed an AIS target about 10nm off our stern that identified as a cargo ship that on current trajectories and speeds, would pass us at just over a mile off our starboard side. I had been having trouble with the radar and had shut it down so thank the stars one more time for AIS. When the ship was within 5nm and due to pass us in about 16 minutes, I called the bridge on VHF radio and spoke to the officer on deck who said that they had seen us on AIS and radar and would I please agree to hold my course and they would pass no closer than 2nm.

Cindy, in spite of being exhausted, relieved me for a bit more than an hour between 04:00 and daylight and the winds and seas were finally getting much calmer. During that watch she saw a ship identified as an oil tanker on AIS that was once again headed our way at a distance still of about 10nm. She called them on VHF but they didn’t answer; perhaps they were still too far away to hear us. When I came back on watch and the ship was much closer I contacted them on VHF as I had done with the cargo ship. This communication did not leave me feeling good because it was evident the person I was speaking with did not speak English or Spanish. Also, their radio communications kept cutting off mid transmission. So I had no confirmation they saw us or that they would hold their heading. As I watched the big ship get closer I fell off the wind some more to give us room. The AIS showed we would pass at closer than a mile. Too close for comfort without communication. Just then, I could see from AIS that the ship was altering course to starboard which now gave us 1.8nm clearance when we passed and I felt confident that he was responding to us and giving way. By this time, the wind and sea had calmed much and we furled in the staysail and deployed the headsail. This was just right for a well needed break and we were still moving along at 3 knots on ever smoother water as the first lights of the morning appeared to the east. We continued on to within about 3 miles of the bay, then started the engine and made our way into the anchorage. By the time we were safely at anchor and had done all that needed to be accomplished we both went to bed for several hours.

Cindy’s Observations:

Rick and I went through the same experience together but walked away with different perspectives on that night rounding Cabo Corrientes.

Maybe it was because my chronic hip/leg pain was really acting up due to my choice not to mix the medication for it with the anti-nausia medication I took for the crossing, or maybe it was the anti-nausia medication (a powerful truth serum concoction) playing tricks with my brain. Or maybe I was just out of sailing shape after 6 months of wasting away in Margaritaville. Or maybe it was that our usual 3-hour on, 3-hour off watches were constantly being interrupted by sail changes. Or maybe it was because my manual steering was impaired because the light on our compass was out so I couldn’t see the compass without focussing my headlamp on the compass while standing, which hurt my leg even more, but the alternative of using the autopilot was running our batteries down and causing us to come uncomfortably close to jibing. Or maybe I was upset that the soup I labored over making in advance for this special night couldn’t even be enjoyed by either of us, let alone together, because it was impossible to eat it without spilling it. Or maybe I was angry because all the weather experts promised only half this much wind. Or maybe it was that in one of the many violent tossings about inside the cabin, my ipad went flying off the nav table and the glass shattered as it hit the sole, while in the meantime, my box of toiletries ended up all over the head floor. Or maybe it was just that I was beginning to feel my age.

No, you know what? It was none of those things. Instead, it was Rick going to the bow to adjust the rigging without my being able to see him, while I was battling 30 knot winds and 8 foot seas manually steering to keep us in a safe course to minimize his being thrown about, not knowing if he had managed to avoid being thrown overboard until he returned to the cockpit. Yes, that was it. That was what put me over the edge.

There was that moment about 10 pm at night when my shift was over and I lay down in my bunk that I literally thought I had never ever felt worse in my entire life than at that very moment. Every inch of my body ached – I could barely swing my legs over into the bunk. I was certain I would vomit if I even rolled over. I was already sick of the constant rolling and being tossed about, and the night had barely just begun. Honestly for the first time since I had begun sailing seven years ago, I felt like I wanted to quit. Right there, right then, just quit.

But of course, I couldn’t. As one of my salty sailing instructors once replied to a student who proclaimed while at sea that she quit, “Quit? You can’t quit! This is the ocean!” As I lay there unable to sleep but just about arriving at a moment of calm paralysis, finding whatever solice there was in the escape from the intense 30 knot winds and 8 foot seas throwing me around, about 11 pm, Rick called me that he needed help. After only an hour into my three hour break, the entire navigation system went down, and in rebooting, it went haywire. Rick had been trying to get the chartplotter orientation adjusted, and in the process, appeared to have touched a bunch of buttons that reset a number of settings, including filling half the screen with useless data, blocking his vision of any obstacles ahead. He called me up to fix it. A part of me was so angry that he called me up for such a relatively minor problem, that I wanted to chew him out. But we have a pact, Rick and I, that if we are ever on watch alone and feel the need for whatever reason for help, we will not hesitate to call the other, and the other will not hesitate to be there. So I got up, put my clothes back on two hours before I was due, went into the head and vomited, and proceeded up on deck to see if I could solve the problem.

If I am painting myself as a martyr, the truth was, au contraire. It is Rick who risked his life at least five times that night by going forward in seas and winds too strong to be going forward. Yes, eventually I solved the chartplotter dilemna. But meanwhile, as I was up on deck with him, we both agreed we needed to shorten sail yet again. We so far had done all the right things: we had reefed to reef one on main and headsail at the first sign of gusts to 18 or so knots, back in the late afternoon. Then, when I was on watch from 7 tp 10 pm, Rick came up on deck about 9 pm and asked if I thought we should reef down to second reef. I said yes, but had hoped we could hold off until 10 pm for shift change so he could get some rest. Instead, he came up at 9 and we reefed down to second reef. But that was not without it’s own challenges. When I eased the main halyard to drop it down to the second reef, the halyard got wrapped around the spreader and wedged between the mainsail and the spreader. We learned then that tension on the tack reef line was needed before easing out the halyard. This was one of many times when Rick had to go forward to figure out a way to solve the problem. He managed somehow to swing the halyard around the spreader as I steered up into the wind with the mainsail sheeted out. Of course, when you head up, the apparent wind becomes stronger and you feel like you are headed into a hurricane, but no matter, we succeeded. But my sacrifice of having to be stirred out of my paralysis during my resting period pailed in comparison to Rick doing the heavy lifting of going forward on the deck in those winds and seas.

Not long after we reefed down to reef two, we realized that still wasn’t enough. This time, we decided we would douse the main completely and just sail on the jib. This was because we were going faster than our boat was supposed to be able to go and she was getting harder to control; she was rounding up, holding onto the wheel was a struggle, and the autopilot, when engaged, was wildly varying course. We sheeted out the main and headed up to release pressure on the main, but once we released the main halyard, the main wouldnt come down. It started flogging in the wind, loose and pressed against the shrouds, but unwilling to drop. So once again, Rick went up to the mast and manuallly hauled the mainsail down with his bare hands. And once we saw that we still had a heavy helm even while sailing just on the jib, we shortened sail yet further by deploying the staysail and furling in the job. We were still maintaining up to 6 knots on just one little hankercnief of a sail!

And then there was the matter of our heading versus the preference of not jibing again. We were on a deep broad reach, so as long as we had the mainsail deployed, to avoid an accidental jibe, we had our preventer set. But to set the preventer as we currently have it configured, one has to go all the way up to the bowsprit to set the line. And every time we jibe, the preventer has to be released and then reset on the other side. And because Rick was concerned about chafe, he put a chafe guard on the preventer at the bowsprit that he didn’t want to lose, so that meant going to the bow twice for every jibe, once to release the preventer and once to reset it. We had sailed out to sea in the late afternoon, and first jibed back in when it was still light. It was marginally more comforting to me that at least I could see him while it was still light, but I was still imagining the scenario of how I was going to retrieve him if he fell overboard, and that freaked me out. He was tethered to a jackline, so that means if he got swept overboard by a wave, he would be dangling off the bow being beaten agsinst the hull until I could bring him in. The thought completely unnerved me. But he had managed not to fall overboard on that first jibe. After that, the wind started clocking so it looked for a while like we wouldn’t have to jibe again – we could make it to our destination on this same tack. But only if we kept the boat on a really really deep broad reach, too deep in my opinion. We were sailing downwind at about 178 degrees off the wind – of course, 180 degrees is dead downwind. And the problem with that is that you can accidentally jibe under those conditions. But of course we couldn’t accidentally jibe because we had the preventer on. Now, it has never happened to me yet, but there has got to be a scenario where even the preventer doesn’t prevent a jibe if you get the wind on the wrong side. I would imagine that what could happen is that the mainsail violently backwinds and throws the mast flat against the water in a semi-roll. That is why you never have a stopper knot on a preventer line, in case you have to release it if things go terribly wrong. Well, during that early shift of mine, I was trying to hold the deep broad reach as best as I could so that we wouldn’t have to jibe again and I wouldn’t have to bear the thought of Rick going forward, but on the other hand, I was having mini-heart attacks every time a wave threw us over the 180 degree mark to the wind, fearing the mainsail would backwind. As it was, the jib was winking like crazy, a sure sign we were too deep. Finally, after three hours of that agony, that is when we decided we had to jibe anyway. And shortly after that, we doused the main so it was no longer an issue.

So all in all, the night we rounded Cabo Corrientes was extremely stressful for me. It wasn’t fun. And why were we doing this if it wasn’t fun? I really had second thoughts. But then we arrived in Chamela.

Hey Guys!! How EXTREMELY exciting!! Also very well written considering all of the variables you are dealing with. I was on the edge of my chair with both perspectives. I continue to be amazed at the practical lessons learned outside of the class room where a passing grade would not have been at all helpful in the resolution of the task at hand. I continue to lift you in prayer for calm seas with a favorable breeze!

Missing you!

/Kent

Dear Rick and Cindy,

Hope you are doing well. I have to write you some sad news about our friends Ria and Waldy. We just read today in a Dutch newspaper that 2 bodies were found close to the coast of San Andres,probably Nicaragua and that their boat was drifting in that area. They seem to be Ria and Waldi from Talagoa,that was mentioned in the article. It is not clear yet what happened to them. Maybe you had heard about it already. We are quite shocked by this news.

Yes we heard. It definitely was them. So incredibly shocking and sad. Where are you now? We will be in Paradise by early July.

Great accounts of a challenging night at sea. I bumped into a YouTube of the boat tour of Cool Change that a fellow cruiser did while you were in FP. I’ve spent the last 4 hours reading randomly chosen blogs from your site. I am heading from San Diego to La Paz in mid November on my Pacific Seacraft 37 and have found all of your blogs quite interesting. I’ll bookmark your blog site and read more from time to time.

I am inspired by both of you and what you accomplished. I hope that you get back to Cool Change soon and that all goes smoothly in the next chapter.

Fair Winds,

Tiemo von Zweck

Thank you! How was your trip down to Mexico?