A 2002 Tongan cruisers guidebook raved about sailing in Vava’u, Tonga, but added the caveat, “The downside, if you consider crowds a negative, are the hordes of cruisers that clog Nieafu Harbor and the closer anchorages.” And admittedly, although I wouldn’t have described them as “hordes,” it was difficult getting a dinghy spot at sunset alongside the floating dock at Mango’s, the most popular cruisers’ hangout, back when we were here in 2019.

Well, COVID, cyclones and the biggest volcanic eruption in centuries have changed all that. Mango’s dock got torn off in the 2020 cyclone, and the place closed up. But more importantly, because Tonga closed its borders in 2020 at the first sign of Covid, had a big Covid outbreak when the rescue workers came after the January, 2022 volcanic eruption, and as of July, 2022, still hadn’t opened their borders to foreigners, we find ourselves in a forbidden sailing paradise! As of August 1, they did make a limited border opening for flights, but the maritime borders are still closed. What this means is that we are in the unique position of being one of the only sailboats on the water here. No one would have believed me had I made this up: a worldwide pandemic closed the borders to one of the best cruising grounds in the South Pacific, and only because our boat was here before the pandemic began and a sympathetic Tongan Consulate worker felt sorry for us, we are now free to enjoy these very cruising grounds all to ourselves! The whales who mate and give birth here, no longer frightened off by the whale-watching boats circling them, have re-entered to play in the most inland waterways of the group, much to the delight of both the locals and us! There is no having to maneuver around even one other boat in any anchorage. Miles and miles of beaches on uninhabited islands await our discovery, with interesting shells accumulating untouched for years. Islanders and expats alike, treat us like royalty because we are a novelty they haven’t experienced for over two years, and we represent a glimmer of hope that their economy will pick up again soon. We have gotten to know most of the major players in the expat community here, who have welcomed us with open arms.

We had been so gun shy about trusting the Tongan government’s borders policy that it had been our intention to sail out of Tonga and into the waters of Fiji as soon as possible. Fiji was the first in the South Pacific to open up its maritime borders during the height of the COVID crisis, by designing an effective “blue lane” system of restricted entry ports and self-quarantine. They are quite welcoming to yachts, they have many more yacht services available, they are a lot easier to get to by air, and everyone raves about the diversity of cruising grounds there. So it made sense to sail west 600 miles to get to Fiji as soon as we could.

But then we went sailing. We had forgotten how wonderful sailing is here! The reason that the Vava’u Group in Tonga is such a unique wonderland for sailing is that the entire island group is enclosed within one gigantic reef that abruptly dissipates the ocean swell. And even inside the group, the frequency and random scattering of islands prevent fetch from building up. So sailing between islands within the group is like sailing on a lake – no swell, no fetch, and just a few wind waves. For those who have sailed in the Society Islands in French Polynesia, the water is like sailing inside a lagoon there, except that in the Societies, the lagoons are too small to really get much sailing in.

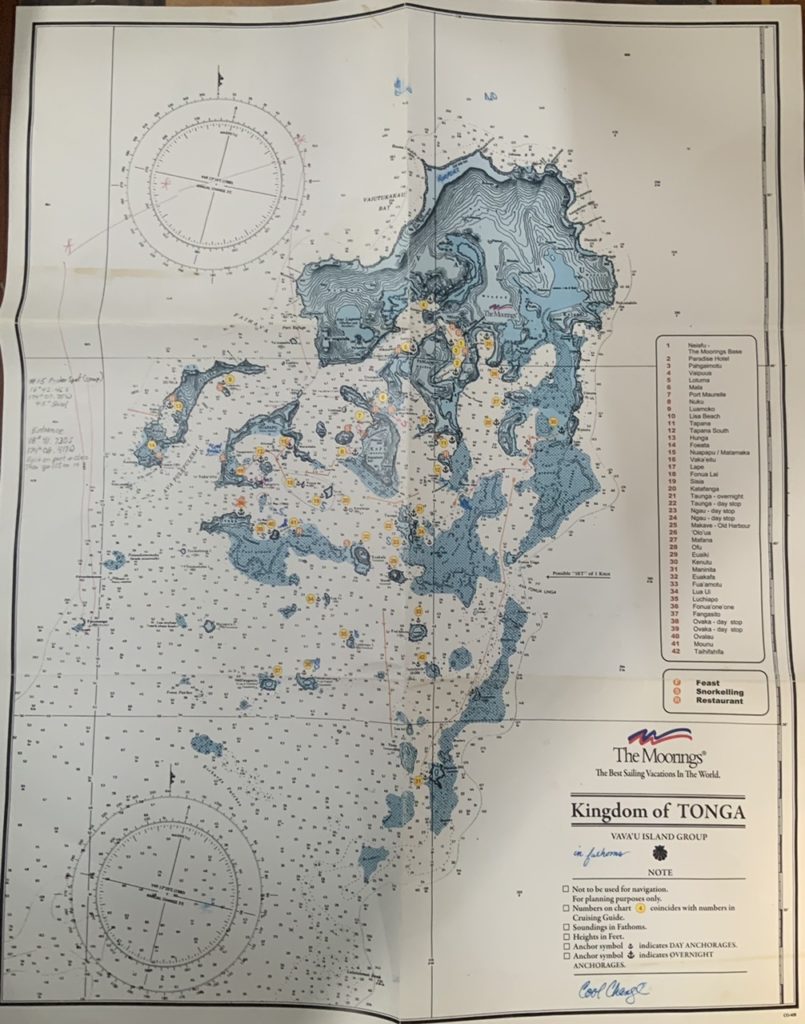

It is fun, active sailing too, because the tradewinds blow right through here, often with winds in the high teens to mid-20’s. You are regularly changing course around one island or another, and the islands create their own weather of gusts and calms. The Moorings charter company, although no longer active in Tonga, left behind the legacy of having identified 42 different anchorages scattered throughout the 12 mile wide by 10 mile long group, anchorages where you can snorkel right off your boat into a nearby coral reef, or dinghy into miles of uninhabited beaches sprinkled with fascinating shells. There are caves to explore, remote lodges to visit for a snack or a drink, and invitations to be had from the locals for church, dinner or other island festivities.

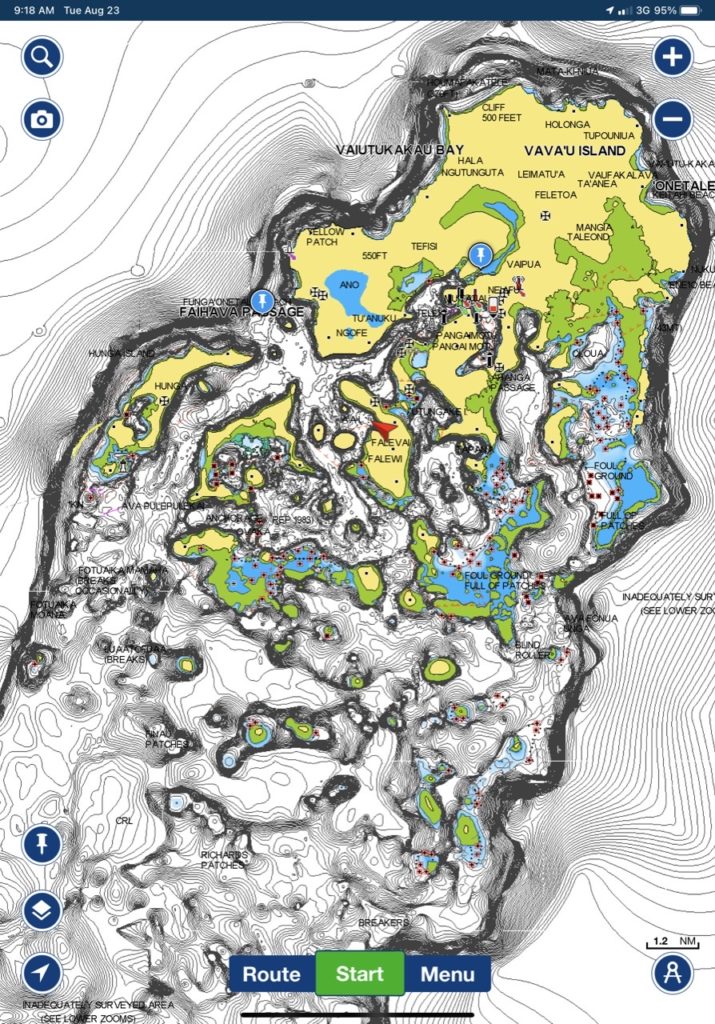

And navigation is important here too: while it looks like it is deep enough to sail between certain islands or in many wide open spaces, it turns out that there are reefs everywhere, so the nautical chart looks very different from what you see with the naked eye. This also makes the 12 mile crossing of the group from West to East, or back again, for example, longer and more interesting than if it were a straight shot. It is often a matter of seeing a place you want to go just a mile or so away, but having to sail ten miles to get there because an impassible reef lies in the way. To get to the easternmost islands, you must negotiate through a narrow, unmarked pass in a zig zag pattern with the sun behind you and a spotter at the bow to avoid patches of coral just below the surface. Fun!

Throughout the month of August, we still had lots of smaller recommissioning projects to catch up on, and there were some pretty big winds that kept us on the mooring near town for part of the time, but we nevertheless got ourselves out sailing on 11 different days, sailing over 100 miles in total.

We headed out to Vaka’eitu Island, only about 7 nautical miles away from the principal mooring field in Nieafu as the crow flies, but a 15 nm sail around islands and reefs. Back in 2019, we were treated to a pig roast with the other boats in this anchorage, hosted by David and his wife Higa. David’s family has had rights to this island for four generations, ever since his ancestor arrived in Tonga from Germany and was gifted the island by the King. David and three generations of his family are the only inhabitants of this large island.

This time, we were the only ones in the anchorage at Vaka’eitu. David greeted us with a basket full of coconuts and papaya picked from his crop, and invited us to lunch with him and his wife the next day, Sunday. David and Higa have 11 children, including one who found himself in California as a missionary when COVID hit. That son then went on to marry and have a child with a woman of Mexican heritage. We arrived on the beach at 1 pm on Sunday as instructed, but David hadn’t gotten back from church yet – he and the other men from the village were indulging in Kava after church, as they often do. When David got back, we chatted for a while and then a few of their older daughters set Poisson Cru and sweet potatoes on the table for us, along with tepid lemonade. The fish for the Poisson Cru had been caught the night before by one of their sons. We ate with only the four adults – the kids had eaten earlier. Higa showed us the leaves hanging nearby that she was drying to weave mats with other women on a neighboring island, and David asked if Rick could take a look at his electrical connection. They had a few solar panels that powered a battery for a few lights and one outlet, which is used mostly to charge David’s cell phone. The electrical connection was working when Rick looked at it so there was nothing to fix. They live mostly outside, but they did have a roofed structure supported by unmilled poles, and walls made of corrugated sheet metal with a dirt floor. They cooked with wood.

One has to be careful not to be judgmental about the differences between David’s family’s standard of living and ours. A consumeristic society, Tonga is not. But all that means is that “things” have a lower priority in their lives than in ours. One could argue, that is not a bad thing. We did want to give back, though, for their generous hospitality, so we loaded up with as many “things” as we could to offer from the meager supplies on our boat that might be useful to them – a bag of lightly used batteries, some jewelry, a cutting board, mechanical pencils for the kids’ schoolwork, fishing supplies, etc. But when trying to repay a debt of generosity with material things in a society that does not value things, you always come up feeling that your gifts are inadequate. Nevertheless, we did our best!

From David’s, the next morning we sailed over to Mounu Island, where we anchored downwind of an aqua-colored reef and dinghied over to a beach, where a table had been neatly set up for us under a palm tree for lunch. Kirsty, a world famous kitesurfing champion, inherited the Mounu Island Resort from her parents, who passed away fairly recently and are buried on the island. She has a lot to handle on her own – a nice lodge, four cabins scattered around the island, an all-inclusive resort environment and a whale watching business on the side. She is quite the woman!

Kirsty’s parents arrived on a power boat in 1996 from New Zealand and fell in love with Tonga. They found the whales irresistible, and her father dove in to swim with the whales one day. He discovered how gentle they were, and wanted to share his experience with his friends, and later, with paying customers. Thus, a new industry was born in Vava’u, swimming with the whales. It became quite a popular industry, and one of the biggest draws to come to Vava’u outside of sailing and fishing. It also represented a huge paradigm shift for the people of Tonga: before Kirsty’s father came along, whales were considered, at best, a nuisance, and at worst, food. Now, whale watching has become an economic incentive for environmental sensitivity.

Kirsty’s dad obtained the 50 year lease on Mounu Island from the King for the price of a pig and two tuna. We walked all the way around the island, which Kirsty said would take about ten minutes but we spent more like a half hour. She walks around the entire island daily, cleaning and raking the beach.

Kirsty is also an accomplished chef, and made up a delicious smoked wahoo salad for us for lunch. She left a pair of binoculars on our table so we could watch the whales frolicking in the bay in front of us while we ate our lunch. Rick had at first balked with me at the price of the lunch – about $20 US each – but once we found ourselves comfortably seated under a palm tree being served a lovely lunch while watching the whales, he changed his tune. This IS the life!

The weather was calm and the Mounu anchorage was gorgeous, so we debated about spending the night there, but we had other plans – we wanted to take advantage of the calm weather to anchor near a cave we wanted to visit the next morning. So late in the afternoon after a leisurely lunch, we motorsailed in light winds downwind to the Port Maurelle anchorage. This anchorage is very well protected and the closest anchorage outside of town, so in years past, it has been packed with boats. But again, this time, we were the only ones there.

In late morning, we dinghied about a mile and a half from the anchorage to Swallows Cave. This is a gigantic cave with a deep water, wide entrance into the underbelly of the tip of an island. The ceiling is at least 50 feet high and the width is probably about 100 yards, with stalactites hanging down from the ceiling but not low enough to get in your way. It is so big that the light coming through the entrance only illuminates a small portion of the cave. It is a fantastic natural wonder, but since boats are the main mode of transportation on the island group and every teenager learns how to drive one, kids have graffitied the inside walls with their names and dates. Partially for this reason, Rick chose this spot out of everywhere we have been in Cool Change, to leave the remains of our nephew Christian, who died a premature death as a young man. Rick could see Christian having come to party with his friends in this very cave. So we videoed our short ceremony and dropped a miniature urn with Christian’s ashes into the deepest part of the water within the cave, overseen by what looked like a sculpture of a guardian angel’s face made out of stalactites. May you Rest In Peace, Christian.

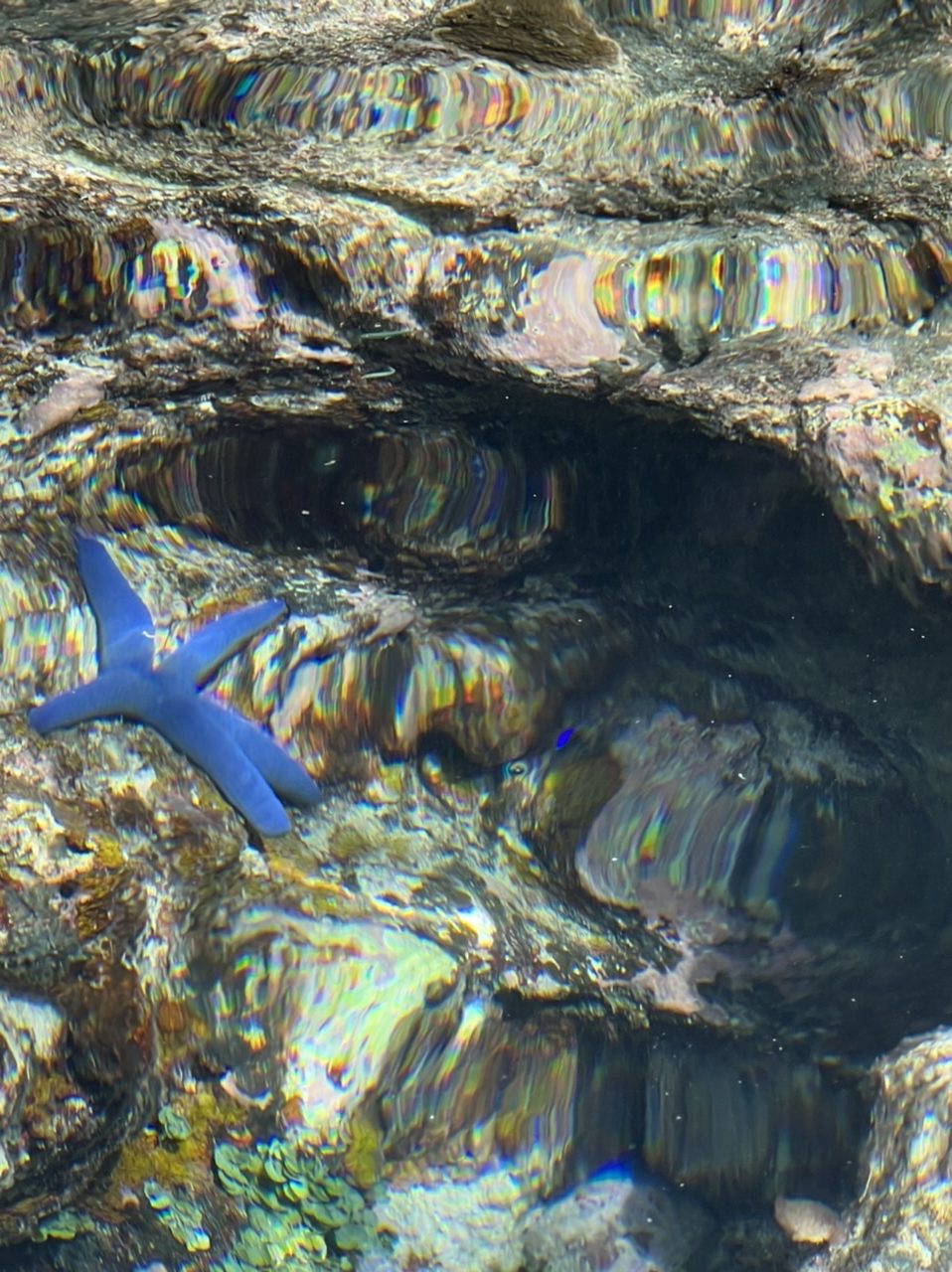

On our way back to Cool Change, we dinghied over to the shoreline where coral outcroppings had formed a sweet little cove of aqua water populated by all kinds of colorful reef fish and starfish. We tied ourselves off and shared a lime-infused papaya while enjoying the scenery, which included bats hanging upside down from a nearby treetop. Bats have been declared by the King to be sacred, so they are left unharmed to fly (and hang) throughout Tonga.

The next day we were sailing upwind, tacking back and forth, making a zigzag track to cross through a narrow pass precisely in the deep water between reefs off of the islands of Kapa and Taunga, when Snap! Rick’s clothes-pin warning system that something was on his fishing line, popped off its clip abruptly. We were in a critical point in the pass and couldn’t change course to slow us down, but I quickly sheeted out the main to try and provide some brakes while Rick got to his hand line and started pulling whatever it was, in. Rick tugged on the hand line, trying to keep tension on the line so the fish wouldn’t spit out the hook, until it came time for him to grab the gaff and bring the fish aboard. At that point he handed me the line and told me to keep pulling the fish in. Well towards the end of the line, the thick black line turned into a smaller diameter line that cut my fingers as I tried to pull on it, and the fish was getting more violent than ever, but somehow I was able to keep tension on it until Rick was able to gaff the fish and bring it on board.

“Whatever is was” turned out to be a 5.3 kilo tuna! Fortunately, it made less of a mess than some of the other fish we have caught in that it didn’t bleed much, and being a tuna, it didn’t have scales nor a lot of random bones so it was a lot easier to fillet. Somehow I have assumed the task of cleaning the fish that Rick catches, and while I am never quite enthralled with the idea, I have learned to cope as best I can: I move away all the cushions from around me in the cockpit; get my fillet knives, cutting board and baggie ready; tie my hair back; take my watch and my ring off; and get completely naked! It is a lot easier to get fish off my skin than it is out of my clothes! Rick helps as best as he can by fetching buckets of water and throwing the entrails overboard for me. Needless to say, I make a much bigger mess than a professional fish cleaner would, but we managed to get four large dinners for two out of that tuna, including some very chunky steaks. And most importantly, Rick’s curse of not catching any fish for some time now was finally broken.

Later on we consulted with enough experts to discover that it was a “dogtooth” tuna we had caught, which are known to hang out near reefs. It is distinguishable by its sharp, triangle-shaped teeth. Although the meat is white, the bones are few, the taste is mild and the texture is firm, all around an excellent fish for eating, it is often not eaten because of fear of ciguatera, a parasite that grows on unhealthy reefs that is toxic to humans. Fish who hang out near reefs are more likely to be infected with it, although it doesn’t hurt the fish. It is undetectable, not killed by cooking, incredibly painful and can cause permanent nervous system damage, not to mention the unfathomable symptom of reversing the sensations of hot and cold. Ciguatera is a problem throughout the world, especially around unhealthy reefs. Fortunately for us, we would have shown signs of poisoning within a few hours of consuming the fish and we didn’t. Besides, Ciguatera tends to be a problem in localized areas where the reefs are damaged rather than scattered uniformly around the world, and Tonga has had few reported cases. Nevertheless, I would feel more comfortable eating a truly pelagic fish like Wahoo or MahiMahi than a fish that hangs out near reefs. I guess ignorance was bliss in this case; had I known beforehand that it was a potential carrier of ciguatera, we might not have enjoyed four great dinners.

On one of our other sailing outings, we anchored in the beautiful and well-protected Tapana Island anchorage and dinghied over to what had been the Paella Restaurant, owned by Maria and Eduardo, from Spain. They were some of the first Palangi’s (foreigners) of the current crop to settle here, back in 1989. They established their family here, and their son opened the Basque Restaurant in town. The Paella Restaurant is on all the maps of Tonga, including Google. When the Moorings charter company was in its heyday, they would send their customers over to Tapana bay to eat at the Paella Restaurant – it was a nice day sail over and a very secure anchorage in almost all weather. The bay was so popular that there was even a floating art gallery in the bay for a while. Back in 2019, we ate at the Paella Restaurant several times, including when our son Dan came to visit. Maria served a several course dinner with interesting and stylish tapas, and then a big pan of Paella cooked over a wood fire. Meanwhile, her husband Eduardo entertained us on his guitar with an eclectic mixture of Spanish ballads and American pop music with quite a liberal interpretation of the lyrics! Maria is also a musician but was too focused on being the chef to be able to entertain us with her music the nights we visited back then.

Anyway, Maria and Eduardo, like us, were stranded out of the country when COVID hit; they had gone to Spain for Eduardo to have surgery. They couldn’t get back into Tonga until just this last May, in spite of incurring all the expense of staying in Fiji for six months in 2021 in hopes of a promised repatriation flight that never happened. Meanwhile, they enjoyed their time in Spain and found some work there. They also came to the realization that at their age, they could no longer keep up the restaurant as well as the maintenance of the four cabins they have on their property on Tapana. So when we saw them, they sat us down to chat for a while, and they reminisced about old times when they would throw big parties at the restaurant that lasted all night. Then they went on to say that they were working hard trying to put the restaurant back together after over two years of abandonment in order to find a renter or buyer so they could return to Spain. And if they found no one to take over, they would simply abandon it. They just wanted to live out the rest of their lives in peace without as much work as their life in Tonga required. No more Paella – it was time for the next wave of entrepreneurs to take over, Maria said.

I found somehow a kindred spirit in Maria, maybe because she was expressing some of the same concerns about running the restaurant as Rick and I had about crossing oceans – maybe our time had just passed; that ship has sailed, as they say. She spoke of no longer making plans for what she would achieve five or ten years from now – she was content with working on being happy for the next five or ten months! I was sad to see the Paella Restaurant no more – it signaled the end of an era that had started over 30 years ago. But it was reassuring that we weren’t the only ones whose lives had changed during COVID, and that it was ok to accept those changes rather than fight them. It’s ok at our age to just simplify our lives, live for today and enjoy life without always planning for the future.

Between visits to various islands, we also found ourselves most every morning and every evening in lovely settings all alone, enjoying the beauty of our natural surroundings or keeping ourselves busy with cooking, boat projects or entertainment. There were rainbows, glistening aqua reefs, interesting marine life, papaya for breakfast and outdoor movies in the evening.

And when we were on the mooring in town, even though we talk of cherishing our time alone on the hook, it was nice for a while to share the mooring field with another boat from the boatyard that had just splashed too: Patty and Steve from Hawaii on their boat Kaelani. They were lifelong sailors and delivery captains who bought this most recent boat in Croatia and sailed it from there – a large, fast, French production monohull that had previously been in charter. They sail four months per year and are making their way West. He is a world-class surfer, now in his 60’s, fit as can be, and she is in great shape herself, especially considering she is my age! Perhaps because of their extensive sailing experience or maybe just based on personalities, they seemed comfortable with a lot more uncertainties sailing than we were: they splashed out of the Boatyard less than a week after they arrived without much prep, even though their boat had been on the hard longer than ours had. They had no SSB (long distance radio), and they had a Sat phone that couldn’t call out. Their throttle cable dangled from an anchor mounted on the stern. But I suppose that is part of what made them fun to be with. We felt instantly connected with them and spent a good amount of time having sundowners together. We even went sailing briefly with them on their boat. They were an inspiration. It was sad to me when they left for Fiji, but maybe out paths will cross again.

As for the sale of Cool Change, there has been some interest, and we may be visited by a few prospective buyers when we arrive in Fiji; Vava’u, Tonga is just not an easy place to fly into right now since there are currently no international flights into here, and the domestic airline is unpredictable. And there has been a huge interest in representing us as a broker. However, we would kind of like to enjoy Fiji for a while before Cool Change is sold, and we had to prepare for storage of Cool Change during Fiji’s fierce cyclone season in case she didn’t sell. That meant we had to put a deposit down on a very expensive cyclone pit, and the final payment is due on September 15. Once that non-refundable payment is made, it makes little sense to waste it by selling the boat before the 2023 sailing season. Besides, we would like to understand better the process of selling a U.S. flagged vessel in Fiji to a foreign buyer so that we make sure we comply with any requirements. So the sail of Cool Change is sort of on hold, although in the right circumstances, we could make an exception! Meanwhile, we are continuing to love every minute we spend with her.

Hi,

I saw the map and comment about the island being completely surrounded by islands.

To enter the island, how do you know where to enter? I assume that the reefs do not extend above the surface everywhere. If not, the depth of the reefs seems an unknown unless the maps are super good. Take it easy. Steve Nemeth

Yes Steve, good question! That is why nautical charts are essential. We use the paper charts for marking our progress on a passage and for overall views, and electronic charts for the details. Passages between reefs are often marked on the chart. And our chart plotter at our helm is like Google maps for the water – it shows exactly where we are and the depths all around us, complemented by our own depth finder instrument.

Plans change with the tide! …the adventure continues ….Your write up was great ….really enjoyed reading ….so as often is the case disaster turns into good fortune and opportunities you couldn’t have imagined. What a fabulous reward for all the stress and work you have endured….these last several months. What a beautiful piece of paradise you’ve had the privileged to be a part of ….Looking forward to your updates as you travel on towards Fiji!

Looks and sounds like a wonderful adventure!

Gail