Departing Vava’u was bittersweet. It felt like we were leaving family behind. Bear and Char from the Falalau Deli froze our home-cooked passage meals and prepared for us a couple of frozen meals extra, in exchange for giving them some wetsuits. Caryl from The Kraken Bar and Grill turned me on to the best doctor in town, without whose help I wouldn’t have been able to depart, due to a stomach bug. Bo from the Yacht Shop charged our new starter battery for us, and she jumped through all the Customs hoops to get our new battery charger to us. As we walked down the street, people we knew honked hello as they drove by. A dozen or more permanent residents of Vava’u knew us by name and it felt like they were there supporting us, taking care of us. The last night as we went out to dinner for the last time at the Bella Vista, and walked back to the dock seeing all the familiar signs of Vava’u, I felt the melancholy of the impending loss of familiarity, combined with no small amount of trepidation for our oncoming voyage.

The next morning we spent our few remaining Tongan coins on some bottles of soda water, and headed down to the Customs agent for our final departure papers. I was certain that the copier must have been broken and the assistant must have walked into town to make the copies because she took so long, but Rick said no, he could see her through the glass window the whole time. Oh well, that is Tonga for you. We weren’t really in much of a hurry anyway.

Normally we would have been required to arrive at the Customs dock with Cool Change to check out of the country, and then the Police boat would have escorted us out to open water to ensure we didn’t make any last stops once we checked out, but this time they made an exception for us. We were allowed to dinghy into the Customs office on the justification that the Vava’u Customs dock is not built for small sailboats and can destroy them – it is built of cement and is too high to approach. Furthermore, their Police boat was destroyed so they couldn’t escort us out anyway; we were on the honor system to leave promptly. And so we did.

We were optimistic about a four and a half day passage of about 600 miles. We were going to have a full moon to light our way at night. All the forecasts were in sync, and showed winds in the 12-16 knot range. Seas were to start out bigger but then diminish. Not much rain forecasted. We were going to be able to update our weather forecasts along the route using our satellite connection on the Iridium Go! And just to be extra safe, we arranged with the pre-eminent weather guru of the South Pacific to give us daily weather updates. We were all set. And even knowing all that, I still had doubts. It helped that my sister Kim had given me a spiritual passage many years ago that I kept at hand for moments like this. I am not particularly religious, but I do find myself turning to trust in God/the universe to provide for me when I have done all I can and still have doubts. It helps. Thanks, Kim!

The route I planned for our trip from Vava’u, Tonga to Vuda Point, Fiji was an attempt to avoid as many potentially dangerous obstacles as possible. We had already marked on our chart plotter, a list of over 40 reefs or other obstructions on our route that had been identified by cruisers but were not on any navigational charts. According to Jimmy Cornell, the author of one of the most well known world cruising route books of all time, “passages between Tonga and Fiji have the reputation of being the most hazardous in the South Pacific, and the number of cruising boats which were lost in these waters confirmed that assumption.” We did not want to become part of that statistic. One of causes for concern is that the eastern border of Fiji is lined with numerous atolls with no lights. Atolls are so flat that they can hardly be seen and are not recognized by RADAR. The entire area area is called the Lau Group of islands. They are very remote, with tribal cultures and few modern conveniences like electricity. Cornell specifically states that “because of the risks involved in passing through Fiji’s Lau Group, boats leaving Vava’u should avoid the more direct Oneata Passage and sail instead through the wider passage between Ogea Levu and Vatua Islands.” So we did! Not only that, but this region is in the center of the seismically extremely active “Ring of Fire” of the South Pacific. New islands can be forming in the ocean right underneath you. I don’t know if it is true or not, but one of the dive company owners in Vava’u told Rick that if you happen to be directly above a developing underwater volcano, a giant-sized bubble of methane gas can rise from the eruption and sink you!

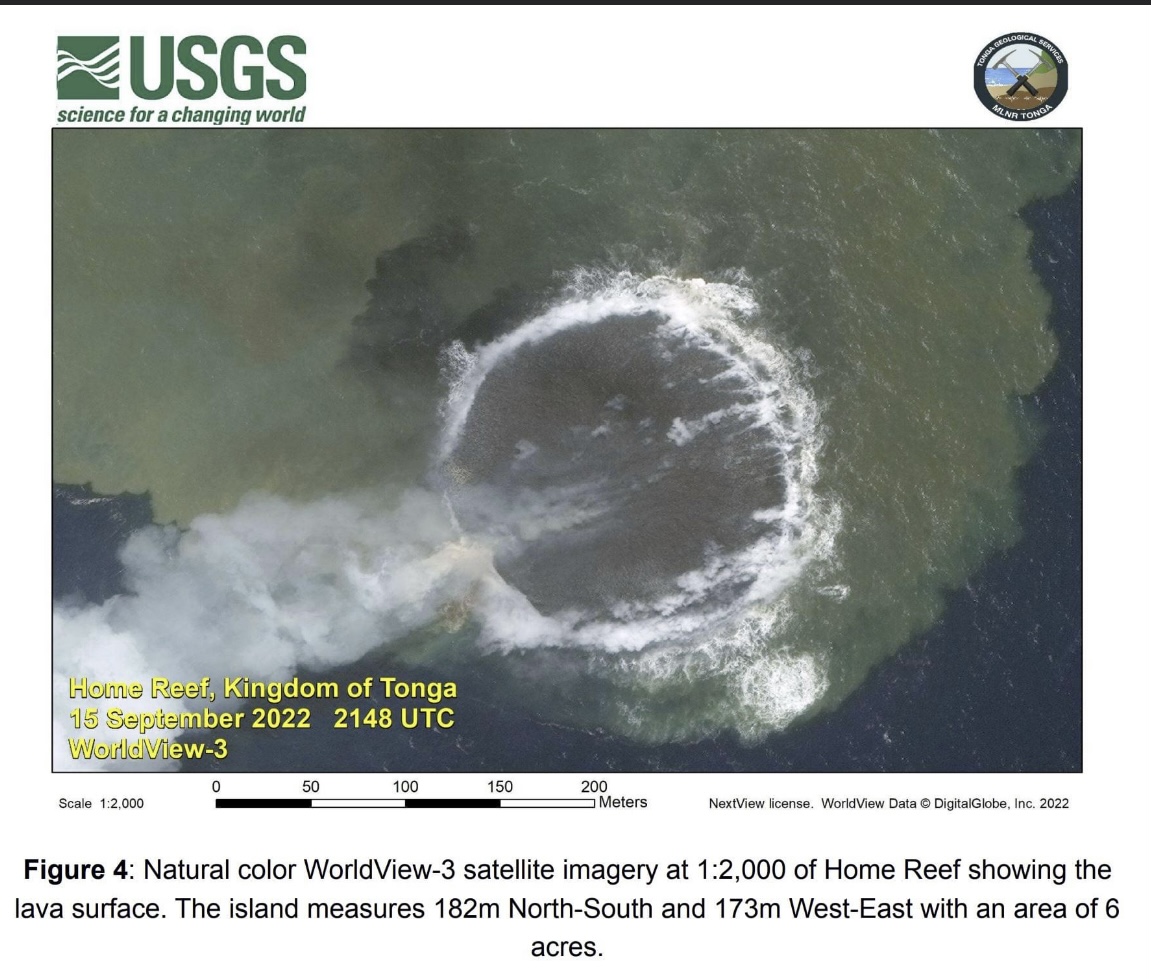

We didn’t find out until later that indeed, in our first day of the passage we came within 15 miles of a new island in the making, called Home Reef. According the USGS, just as we were passing by, ”a volcanic submarine island re-emerged 10 meters above sea level and continues to grow larger, from one acre to nearly six acres in five days, (we passed by it on the fifth day, the same day the USGS photo below was taken) sending steam vents one kilometer into the atmosphere…. The eruption events had increased in the last 24 hours to 11 events compared to two events in the previous 24 hours, thus a total of 13 eruptions in the last 48 hours.” Mariners were advised to sail further than four kilometers from the site. Good thing Late Island was between the eruption and our course, or we could have easily chosen to head in that direction, although we did have the underwater volcano marked as an obstacle on our chart from previous eruptions.

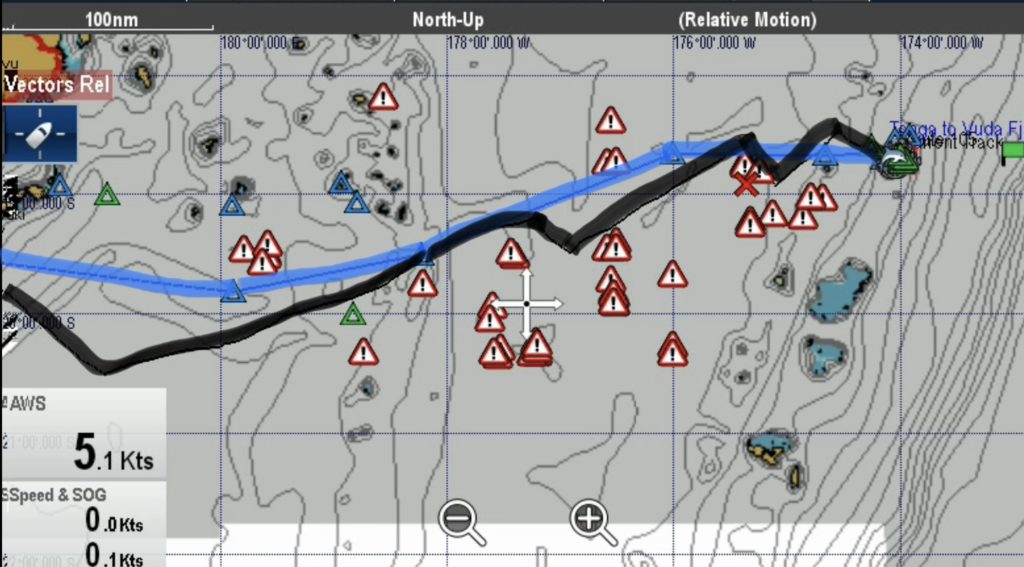

So, we planned our trip as carefully as we could. Instead of taking the most direct route in a straight line, which would have landed us on an unmarked island or reef for sure, we set waypoints out of the way of any known obstacles. And then we put those waypoints into our PredictWind app to give us an idea of what weather we would hit along the way, and what our point of sail would be.

What I hadn’t given much thought to, was PredictWind’s estimate of how deep the wind angle would be for most of our passage. Sailing “deep” means that the wind is coming from almost directly behind you, and you are sailing “downwind.” Well, Cool Change can do that, but only if we sail in a configuration called “wing on wing,” or a little less effectively, with our spinnaker. But both of those sail configurations require fairly flat seas, at least for Cool Change – otherwise because of the rocking caused by bigger seas, it would be too easy to backwind one of the sails and get into serious trouble.

As a result, at least for the first two days when the seas were over two meters and the true wind around 20 knots, we couldn’t sail as deep as our route required, and instead had to gybe back and forth in a zigzag motion to stay more or less on route. In those first two days we sailed 242 nautical miles (nm) to get just 180 nm from Vava’u. All in all by the end of the trip, we sailed almost an extra 100 nm over our intended route of 600 nm, which added almost a day to our passage time.

You can see part of our passage below. The blue line was our intended route and the black line is what we actually sailed. The long stretch on one tack without gybing is when we had flatter seas and were able to sail deeper, wing on wing.

Complicating the control of our direction was the fact that our autopilot had started acting up, not holding a course, even before we left Vava’u. We are accustomed to the autopilot staying the course for us even if the sails aren’t quite trimmed properly to accommodate it, and even if the waves keep throwing the boat off course. It’s only downfall is that it does suck power. We weren’t certain of the cause or severity of the autopilot failure because it was intermittent, but we got to the point where we couldn’t trust it. Rick could have changed out the autopilot with our backup before we left Vava’u, but since we were assured there would be wind the entire trip except at the end, we figured we would just rely on Charlie instead.

Charlie is Rick’s deceased dad’s name, and also the name of our Monitor Windvane steering system (so his Dad can always be with us). This is an apparatus that will steer the boat for you on a particular angle to the wind if you set it correctly, as long as there is consistent wind. It doesn’t need any power from the boat to run it. There are two drawbacks to Charlie, however. He doesn’t really do super well holding a tight course when steering near to downwind unless the sails are set correctly to accommodate that, namely, wing on wing, especially in big seas. He has no way to anticipate sea state influences like the autopilot does, so he bounces us around a lot between different courses, sometimes as much as 30 degrees. His other limitation, obviously, is that he only operates when there is wind.

On the third day, sure enough, by about 11:00 a.m., there was too little wind to sail. We tried to use Charlie along with the motor while the wind at least supported the mainsail being deployed, but it was a challenge. Once Charlie was out of the picture, we were left with either the failing autopilot or hand steering. Most traditional sailors do not baulk at hand steering for long periods, but Rick and I just don’t feel we have the stamina to do so. It takes concentration, constant attention, often standing for long periods, and no time for anything else. Even taking a moment to search for your coffee cup can throw you off course. So mostly we used the autopilot and reset it over and over again every time it failed, cursing ourselves for not replacing it before we left.

It was a relief, though, that the seas calmed on that third day as the winds died, and we could relax a little. The afternoon was gorgeous, and the gentle rocking of the seas made us both feel like babies in a cradle. Rick and I spent the late afternoon together in the cockpit talking and checking in with each other. Our watch schedule was deliberately set up so that we “dog-watched” from 4 to 7 pm – both available to mind the helm but no one assigned. That was partly timed around our two SSB radio net check-ins each day. Rick took the 4 p.m. and I took the 7 p.m. check-in. Those nets made us feel more secure that at least someone knew we were out there, and we could get some advise if we needed it. In fact, our friend Rob from the boat Athanor, who was in French Polynesia, stayed on after the SSB net one night to talk through some boat problems with Rick. We would heat up dinner and eat together during that dog-watch, and discuss any issues that might have arisen during the day that we needed to work out.

I was able to share that I was delighted to find not only that my stomach problems seemed to be resolving themselves, thanks to the medication I got in Vava’u, but also, that my favorite anti-seasickness medication, Stugeron, seemed to be working – I had very few symptoms and hadn’t gotten sick yet, in spite of the rough seas. I was also starting to realize that while I wasn’t having as hard a time as I remembered adjusting to the lack of sleep at night, I was, indeed, moving into an interesting altered state of consciousness where I was never neither completely awake nor completely asleep. I was in a transitional zone where non sequitur scenes from a dreamlike state entered into my conscious thoughts, where hallucinations were not infrequent, especially at night, and where unresolved feelings from past events passed through my awareness as if I were watching them from a moving train, with no control over the scenery. A cow was in a field and then a boy was running and then I was awake, or I awoke to see a wall where the mainsail was and a door where the lifeline gate was. The unresolved feelings from past events were more elusive, but it seemed my subconscious was struggling to find a way of thinking about them that could bring me peace. I told Rick that ocean passages were looking more and more to me like a form of therapy!

So here we were, enjoying the late afternoon together, when Rick looked down and saw that the ignition had completely disintegrated and fallen out onto the floor of the cockpit, along with the key. While the engine was running, mind you. We had a running engine with no key in it, the lock that the key goes into had disintegrated too, no way to shut it all off, and worse yet, no way to turn it back on if we shut it off!

While Rick was still in shock, I suggested we just keep the engine running for the whole rest of the trip, in neutral if we had wind, so that we could have the engine on at the end of the trip when we needed it to get into the harbor. Rick said we likely didn’t have enough fuel for that. We decided to let the engine run all night since we had little wind anyway, and maybe his sleeping on it would give him some insight into a solution. Well, it did. The next morning Rick reinforced to me that this was a relatively simple tractor engine that starts with not only a key but also with a start button, and shuts down by pulling a cable that shuts off the fuel supply. The key lock really only serves to energize the start circuit and to turn on the electric fuel pump. Rick awoke with the idea that on this engine, the key can just be left in the “on” position and the engine can then be run or shut off as needed. He would just need to reconnect the fuel pump on an independent circuit and install an on/off switch for it. So that’s what we did. We haven’t gotten it fixed yet, so right now, that is still as it stands. If we want to start the engine, one of us turns on the new fuel pump switch and the other one presses the starter button that completes the circuit to the solenoid and starts the engine. This is one of those “MacGyver” things that Rick is so darn good at; a solution I would never be able to conjure up on my own.

The longterm solution to the problem was obvious: the ignition switch needed to be replaced. [Status update: we are now in the marina a week later and the ignition switch has not only been replaced, but all the electrical terminals in the instrument panel have been cleaned up and are as shiny as if they were new. The autopilot has also been fixed – some external mounts that are designed to move were frozen, so they have been unfrozen and lubricated. Both of these problems were issues that resulted from Cool Change sitting for so long during the Covid lockout. They would have been hard to anticipate, and required a shakedown cruise like this one to find. We now feel confident that such issues have been addressed]. It is the nature of full time cruising that improvements or repairs are constantly being made to the boat, no matter the value of the boat or its build date; we just had the added challenge of shaking out what final repairs were needed due to the Covid lockdown.

Anyway, back to the passage … by the fourth morning, the wind had picked back up and the seas had settled down enough that we felt comfortable with a wing on wing configuration. Most of the time, a sailboat sails with all the sails deployed on one side of the boat or the other, but with wing on wing, the mainsail is deployed to one side, and with the help of a “whisker pole,” the headsail is deployed on the other side. This made it possible for us to sail very close to downwind, and hold our course with Charlie, while staying fairly true to our intended route. We didn’t loose as much ground on this tack, and held it for a long time. The day was glorious: we were traveling smoothly downwind in the right direction at a relatively fast pace, the skies were clear, we had a temporary fix for the ignition problem, and all was well on Cool Change.

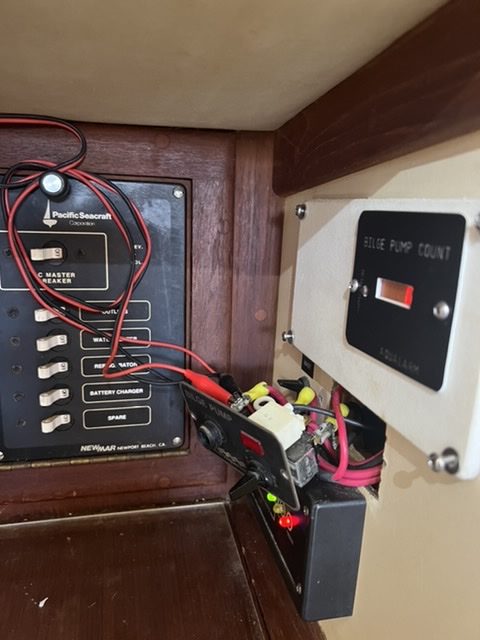

But as the evening of our fourth day approached, things got more challenging again. First, Rick discovered that the bilge pump control panel had failed, which meant that the bilge pump was no longer operating. He was able to rig it to operate manually, but in doing so, he moved the controller out of position and it blocked the full opening of the fridge lid. Furthermore, the toilet was leaking, so we found ourselves having to mop up regularly. [Status update: Fortunately once at the dock, Rick was able to replace the bilge pump controller with an identical brand new one we bought in Fiji, and we found the cause of the toilet leak and fixed that too. In both cases, just as with the ignition and autopilot, the cause was clearly linked to Cool Change sitting for over two years during Covid lockdown.]

And then on my 9 p.m. to 2 a.m. watch that night, I was hitting squall after squall, drenching my first set of clothes. I donned my foul weather gear, only to get those soaked too. The periods of rain were short but quite intense, and I must have gone through four or five squalls. The wind and seas would come up and then drop to nothing as each squall came and went, making me disconnect Charlie occasionally and either hand steer or deal with our failing autopilot. We were still wing on wing, and I didn’t want Rick to go up to the forward deck at night to release the whisker pole even though a more flexible sail configuration was advised by that time. Then I saw a light off in the distance that turned out to be a large, very bright fishing trawler. He was not on AIS (an electronic identification system used by most commercial and well-commissioned pleasure boats other than fishing boats), but I could see him on RADAR. His bearing remained constant as his distance diminished, a telltale sign of being on a collision course. I couldn’t really change course without furling in the headsail because wing on wing limits the boat to a very small variation in course, but I didn’t want to loose the little use I could make of Charlie by furling in the headsail.

Meanwhile, Rick had set a guard zone on RADAR, which means an alarm goes off if traffic enters the zone in front of you. It is a great safety device but I find guard zones a pain in the butt! Unless the target has no lights, I usually see them well before the alarm goes off. On our Raymarine system, after you turn it off, the alarm keep coming back on, repeating itself until you go deep into the system to change the alarm setting. Meanwhile, you are dealing with the real emergency of traffic ahead.

When the alarm kept going off, Rick came up to see if he could help but as I said, the alarm setting was way too deep into the system for him to be able to help, and meanwhile, the alarm for the failing autopilot went off. I was soaking wet, it started raining again, two alarms were going off, I had a dangerous target ahead directly intersecting me on my course, and Rick was in his underwear at my side trying to help! It was not a pretty scene!

I can’t imagine that the fishing boat could visually see us through all the lights they had on their boat, but finally about a mile away from us, they changed course as if to avoid us. When I finally thought they were no longer a danger, they then approached us again, this time from behind, but stopped about a half mile away. Because they rarely carry AIS and have erratic routes, fishing boats are cruising boats’ nemesis. But this time we seemed to have escaped unscathed.

The rainy weather let up before Rick’s 2 a.m. watch started, and he had a beautiful night with no rain and with sufficient wind to sail. He did wake me up to get the windvane set properly, one of the very few knacks in sailing that I have acquired perhaps with slightly more prowess than Rick. We decided to wait until the morning to have him go forward to remove the whisker pole. At first light when my watch started, we furled in the jib and Rick went forward to take down the whisker pole, but by that time, the seas were starting to build again and we were reminded why we don’t use wing on wing more often in open water: going forward in higher seas with just the main deployed is not something you want to do with regularity.

The fifth day was to be our last full day at sea and we were really looking forward to that last waypoint that marked a turn north directly towards our destination. From nearly downwind, we would be turning more into the wind so that we would no longer be struggling to maintain a downwind course. We would be sailing on broad reach, where the wind is still coming from behind you but just by a little bit. (The angle of the wind, for example, was about 160 degrees for the past 100 miles (just 20 degrees off from dead downwind), whereas the new wind angle would be just about 115 degrees (90 would be right from the side, so this would be a little more downwind from that and a little more comfortable). And the wind was predicted to be about 14 knots, quite comfortable. NOT!

We got to the waypoint, revised our heading and boom! we were close-hauled! What that means is our angle to the wind was only about 45 degrees. The apparent wind was not 14 knots; rather, it was gusting to 23. The waves seemed so much bigger because we were sailing into them. It was all very uncomfortable. Charlie had a hard time not rounding up and we were constantly adjusting him while sheeting out the mainsail enough without backwinding to try and appease Charlie. Just as we thought we had gotten the sails balanced, we entered a 30 mile stretch that our weather Guru called a “wind tunnel.” There were two large islands about 30 miles apart off starboard and we think maybe the wind tunnel was caused by wind whipping through the gap between the two islands. In any case, the wind and the waves picked up even more. By this time, I had just gotten off watch at midday and was looking forward to having a little rest when Rick called me up to the deck, asking me to help him put another reef in the mainsail. I assumed this would be a quick assist and then I could go back to sleep, and I wasn’t dressed. So I thought about what I could throw on in a hurry to assist him and I thought of my “Tongan dress.” I call it that because it has sleeves and goes below my knees, appropriate attire for a Tongan church. It is kind of like what we used to call a “moo moo” and easy to put on. So I threw this dress over my head, otherwise naked, put my vest on and went up to assist Rick.

Well when I got on deck, I realized why he thought we should reef – we were hauling ass at more than 7 knots and felt extremely overpowered. Even after we went down to the third reef, it was still hard to stop Charlie from rounding us up. Rick commented that in these conditions, we should probably both be on deck – there went my afternoon nap. As I was trying to position Charlie, I would ask Rick to sheet out to take some power off the sail, and Rick would reply that he couldn’t because the mainsail would get back winded, but it was getting back winded because we were pointing too high because we were overpowered and Charlie couldn’t handle it! It was a catch 22 and kinda humorous when you think about it. But finally we got the sails balanced and Charlie mostly behaved unless a wave he couldn’t handle threw us off course. And each time that happened, I got a wave over me! At one point the cockpit nearly filled with water and it took quite a while for it to drain out. So there I sat in my lovely yellow Tongan church dress with nothing on underneath, my hair not tied back because I hadn’t intended to be on deck for long, soaking wet and salty, and hanging on for dear life. It was all so ridiculous, all we could do is laugh. I went down below to change and wash the salt off my face, and then Rick got drenched too!

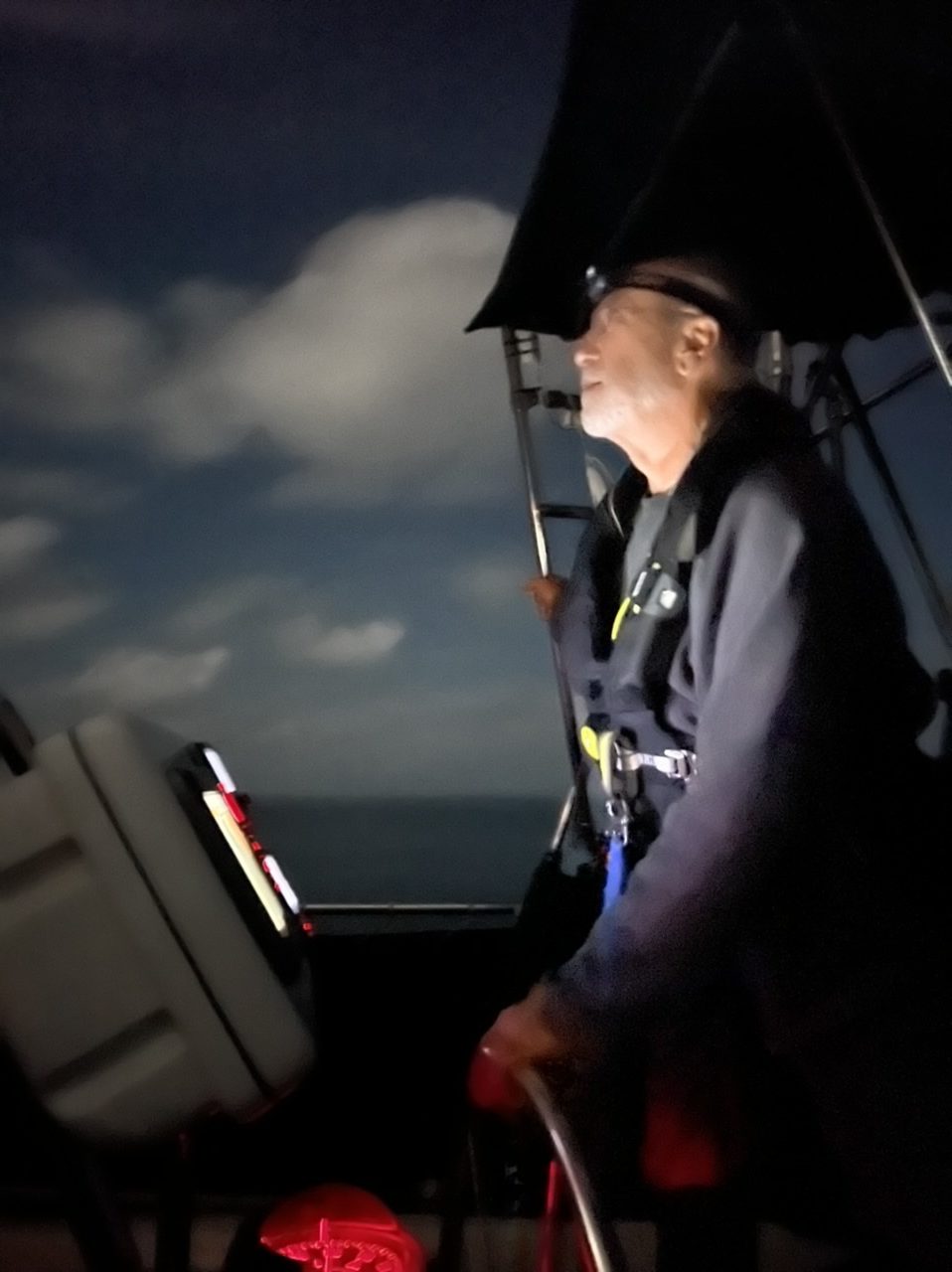

When we finally got out of the wind tunnel, it was quite a relief, but it wasn’t too long after that when the wind died altogether. It was hard to believe that the wind could change that much in one day by just sailing north, but it did. We were starting to get into the wind shadow created by the large Fijian island that was our destination. So as dusk settled upon us, we realized we would have to hand steer all the way to our destination about 11 hours away. We decided the best way to do that was for both of us to stay on deck and take half hour shifts behind the wheel, which is what we did. While off shift, we would rest lying down in the cockpit with a pillow for our head and hope to catch a few moments of sleep during the half hour. I found this process easier than I thought it would be. My wrist watch has a great little alarm that kept track of our 30 minute watches with ease. I was so tired that catching a few moments of sleep for 30 minutes every hour wasn’t hard for me at all, although waking up got harder and harder. Rick figured out a trick of anticipating when the autopilot would fail before the failure alarm went off (i.e., when the actual heading increasingly varied from the locked heading.) That made resetting the autopilot easier and didn’t wake the other who was resting, so we were able to use the autopilot somewhat. I helped that process by setting some of the instruments to provide us the readings in big numbers that we needed to predict an imminent autopilot failure.

By the time we reached the pass that would take us from open ocean to inside the reef 4 hours from our destination, we were both pretty tired. Entering a pass for the first time at night is never a good idea, but we figured this was a major shipping channel so it should be wide enough and well marked enough for us to figure it out. There were some confusing lights at first, and we had to remind ourselves that the “red right return” adage was reversed in the South Pacific, meaning that the red light is on the left, not the right, when going to shore, and the green light marks the right side of the channel. I was confused by a green light to the left of the red light, but then I realized that it was a green light from another approach to the channel. And what really saved us was that there was a “range” set up on the far side of the channel, where two red lights, one above the other, marked how to line up to get through the pass. Rick followed those and voila! we were through.

It was still another four hours or so of motoring to get to our destination, but there was enough going on that we got a second wind, or at least Rick did. There were large ships anchored on either side of the channel that confused us, and RADAR scatter made it look like there were more targets out there than there were. But finally as dawn was breaking, we arrived at the anchorage outside the marina where our quarantine buoy was waiting for us. We were relieved that no one was yet on it. It took us a couple of tries, mostly because I didn’t slow us down enough on our first pass for Rick to grab the buoy line, but eventually we got moored, put up the yellow quarantine flag, and breathed a sigh of relief. We had made it. It was early enough that the marina hadn’t opened yet, so we gathered up all the sheets and dirty laundry, cleaned up ourselves and the boat a little to make us presentable for Customs and Immigration, and waited for the sun to rise on a new day in a new country. Fiji, here we come!

Love reading g about your South Pacific adventures. You two have been making forever memories. ❤

Bula! Congratulations!!! Loved reading about your passage. A favorite saying of my mother’s was”if it is not one thing it is another”. I think that’s sums up your passage well. And why does shit seem to happen when you finally get some down time? Good job letting Rick come up with solution overnight! Sending Hugs! Laura & Dick

Great description of a passage. I did the same passage around the same time, solo, on my PSC34. Tonga was still closed so I sailed around the north via a tiny island called Toku, then through the Lau Group north of your pass (had to stay awake overnight to avoid all the little islands), to Savusavu on Vanua Levu for checkin, then back east to the Lau Group all the way down to Ogea, then back to Suva, and down that rough windy section to the wide open pass into Viti Levu and up to Vuda Point marina where my boat, Sea Change, remains in the cyclone-resistant circle till next season.